The Strange Tale and Travels of Oliver Cromwell’s Head

Oliver Cromwell, a central figure in British history, remains one of its most controversial. As Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland, Cromwell ruled with an iron fist after the execution of King Charles I. However, following the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, Cromwell’s legacy faced a dramatic reversal. His corpse was exhumed and subjected to a posthumous execution, leading to a bizarre and macabre journey for his severed head.

This article explores the strange tale of Oliver Cromwell’s head, tracing its travels, the hands it passed through, and the speculations about its current whereabouts.

The English Civil War and the Rise of Cromwell

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a tumultuous series of conflicts that pitted Parliamentarians, known as the Roundheads, against the Royalists, or Cavaliers. The roots of the war lay in deep-seated disputes over the governance of England, specifically the balance of power between the monarchy and Parliament. At the outset, Oliver Cromwell was not a prominent figure. Yet, as the war raged on, he ascended through the ranks, largely through his innovative leadership and military acumen. Cromwell’s pivotal role in forming the New Model Army, a disciplined and effective fighting force, marked a turning point in the conflict.

His strategic prowess and unwavering resolve helped secure key victories, culminating in the trial and execution of King Charles I in 1649. This act led to the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Commonwealth, a republican form of government.

Lord Protector of England

In December 1653, following the dissolution of the Rump Parliament, Cromwell was appointed Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland. This role granted him extensive powers, and he effectively ruled as a de facto monarch. His tenure was marked by efforts to stabilise the nation through various reforms, including the promotion of religious tolerance (albeit within a Protestant framework), the expansion of overseas trade, and the suppression of Royalist uprisings.

Cromwell’s administration also saw significant military campaigns in Ireland and Scotland, which were both brutal and controversial. Despite his authoritative governance, Cromwell’s rule was instrumental in shaping the political landscape of the British Isles during this tumultuous period.

Posthumous Execution

Cromwell’s death on 3 September 1658 was marked by significant ceremony, reflecting his status as Lord Protector. Yet, the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 brought a dramatic shift in his fate. King Charles II, determined to avenge his father’s death, ordered the exhumation and desecration of Cromwell’s remains.

On 30 January 1661, the twelfth anniversary of King Charles I’s execution, Cromwell’s body was exhumed from its resting place in Westminster Abbey. His body was hanged in chains at Tyburn, and after a day, it was cut down, and his head was severed. The head was then displayed on a spike above Westminster Hall, a stark warning to all who might challenge the restored monarchy.

Travels of the Head

For decades, Cromwell’s head remained a macabre spectacle, enduring the elements and attracting curiosity seekers. However, in the late 1680s, a violent storm dislodged the head from its perch, sending it crashing to the ground. The specifics of its retrieval are cloaked in mystery, with various accounts suggesting it was discovered by a sentinel or a passer-by.

One popular tale suggests that a guard, fearing punishment, took the head home and concealed it in his chimney, a secret he kept until his death.

Private Collections and Public Exhibitions

In the 18th century, the head emerged from obscurity, entering the hands of several notable collectors. Claudius Du Puy, a Swiss-French collector, acquired it and displayed it in his London museum, where it became a prized exhibit. After Du Puy’s death in 1738, the head was sold to Samuel Russell, an actor and museum proprietor, who capitalised on its morbid appeal, making it a popular attraction for the public.

By the early 19th century, the head came into the possession of James Cox, a prominent surgeon. Recognising its historical significance, Cox conducted a thorough examination, confirming its authenticity. He then sold the head to Josiah Henry Wilkinson in 1815. The Wilkinson family retained the head for generations, occasionally showcasing it at gatherings and to interested parties.

An 1822 account described the head’s appearance in chilling detail: “A frightful skull it is, covered with its parched yellow skin like any other mummy, with its chestnut hair, eyebrows, and beard in glorious preservation. The head still fastened to its inestimable, broken bit of the original pole—all black and happily worm eaten.”

Speculations and Theories

The head’s journey through private collections has fuelled numerous theories about its authenticity. Scholars have debated whether the head displayed over the centuries was indeed Cromwell’s. The lack of definitive forensic evidence and the passage of time have made it challenging to establish its true identity conclusively.

In 1875, a head at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum was compared with Wilkinson’s head. George Rolleston, an anatomist, declared Wilkinson’s head the real deal, citing its remarkable correspondence with known features of Cromwell’s visage.

Forensic Studies

The mystery surrounding the head continued into the 20th century. In 1911, the Royal Archaeological Institute conducted a detailed study, comparing the head’s physical features with busts, life masks, and death masks of Cromwell. Their findings, while not conclusive, indicated a strong likelihood of authenticity. The skullcap, removed during embalming, was reattached, and X-rays revealed the presence of a prong, once thrust through the skull, still lodged within the brain-box. The researchers noted, “The accordance between the mean of the masks and busts and the Wilkinson Head is astonishing.”

In 1934, Canon Horace Wilkinson allowed scientists Karl Pearson and Geoffrey Morant to examine the head. Their study, published in Biometrika, focused on the head’s physical characteristics rather than its origin. Pearson and Morant’s analysis, although inconclusive, supported the head’s probable connection to Cromwell, noting the alignment of anatomical features with historical descriptions.

Final Resting Place

By the mid-20th century, the Wilkinson family, weary of the head’s macabre legacy, decided to give it a dignified burial. After extensive consultation with historians, they chose Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, Cromwell’s alma mater, as its final resting place.

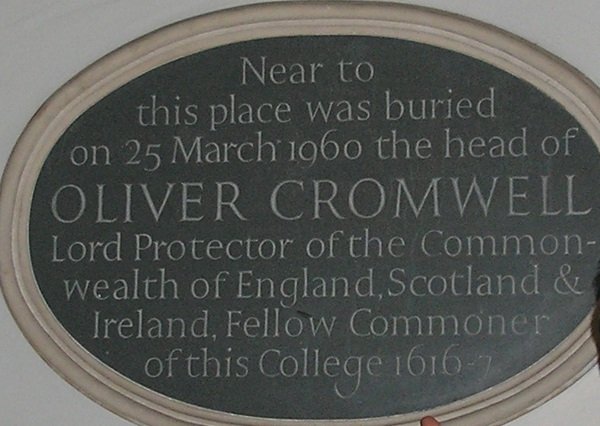

On 25 March 1960, Oliver Cromwell’s head was interred in a secret location within the college grounds. A plaque now stands at the college, marking the spot and commemorating the head’s strange journey through time.

Conclusion

The strange tale of Oliver Cromwell’s head encapsulates the complexities of historical memory and the enduring fascination with one of Britain’s most polarising figures. From its posthumous execution and display on a spike to its journey through private collections and eventual burial, the head has symbolised the shifting sentiments towards Cromwell.

This journey reflects the unpredictable nature of history and the ways in which legacies are reinterpreted over time. The plaque at Sidney Sussex College serves not only as a marker of Cromwell’s final resting place but also as a reminder of the bizarre and often unpredictable nature of history.

Has this article inspired you to visit a paranormal location? Plan and book your visit here.